Chapter 3: Moving More On My Own

#MMOMO

This discussion + podcast is the third of a 10-part series that accompanies our book on SCI recovery, From the Ground Up: A Human-Powered Framework for Spinal Cord Injury Recovery. It will introduce the uninitiated reader to topics discussed in Chapter 3 of the book, but some vocabulary or context may not be fully defined.

Let’s call it as it is: society has an assumption on what recovering from a paralyzing injury looks like — standing and walking seems to be what everyone considers when it comes to healing from SCI.

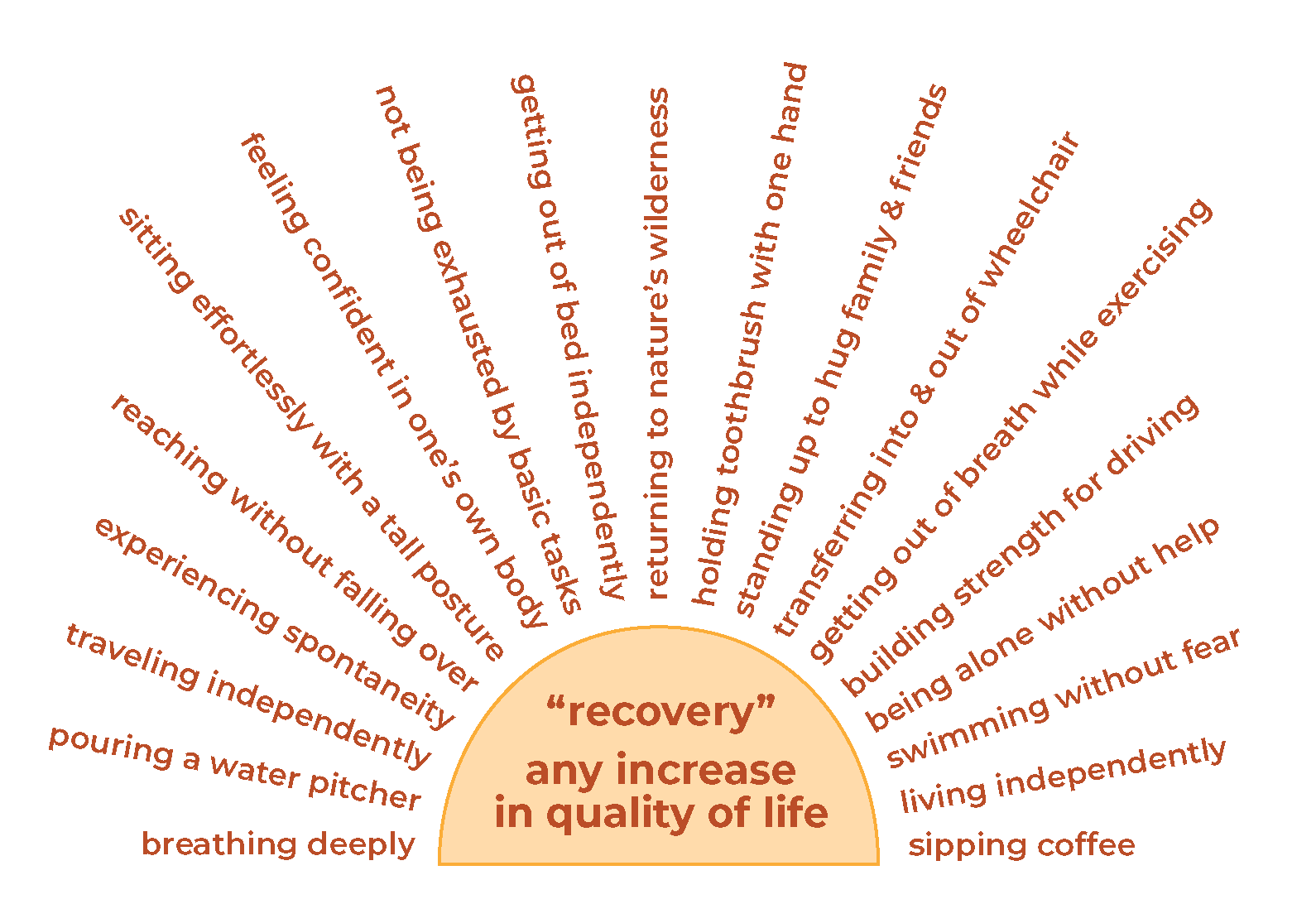

But “recovery after spinal cord injury” means something different to every person with an SCI. In fact, there are several surveys showing us that individuals with SCI care more about getting out of pain, the use of hands, and doing things they enjoy, over walking and standing abilities, overall.

Graphic adapted from Lo, C., Tran, Y., Anderson, K., Craig, A., & Middleton, J. (2016). Functional priorities in persons with spinal cord injury: using discrete choice experiments to determine preferences. Journal of Neurotrauma, 33(21), 1958-1968. DOI: 10.1089/NEU.2016.4423

The reliance on a wheelchair might be the most visible thing from the outside, but it’s often other lifestyle elements are what people miss the most — packing lunches for the kids, impromptu travels, brushing teeth and doing other household chores with ease.

Recovery goals after spinal cord injury take many different forms:

Living independently

Swimming without fear

Experiencing spontaneity

Sitting effortlessly with tall posture

Getting out of bed independently

Standing to hug family

Transferring from wheelchair to tall bar stools

Holding toothbrush with one hand

…and so many more

Spinal cord injury “recovery” means something different for every SCI athlete.

In writing a book about spinal cord injury recovery, we were motivated to define recovery so readers could follow our arguments and motivations. But how can we possibly encompass the breadth of rehab goals after SCI?

We use the phrase Moving More On My Own (MMOMO) to encompass the wide variety of SCI recovery goals because self-generated movement feeds into each of these specific recovery goals (yes, even building self-esteem/confidence in the body you now have can be supported by working on postural control/how you hold yourself physically).

Each component of “moving” / “more” / “on my own” is discussed deeply in Chapter 3 of From the Ground Up – and we’ll introduce the importance of “more” here.

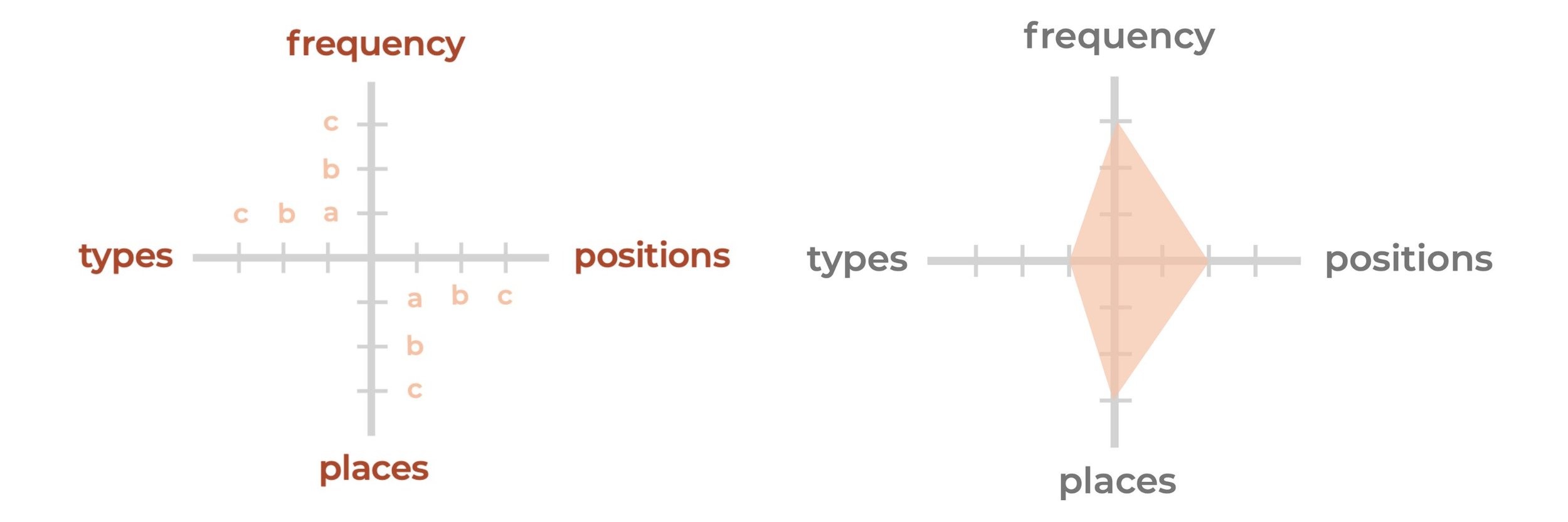

MORE movement: types, frequency, position and places

The SCI community focuses a lot on whether or not someone can accomplish a particular motion, but much less on how well individuals use their movement skills in various contexts.

We want to encourage individuals with SCI to expand the ways in which they move with respect to the type of movement, how often they move (frequency), in what positions they do exercises and where this movement variety takes place:

Type of movement demonstrates control in different contexts: fast/slow, large/small range, choreographed/freeform

Frequency ranks how often the individual uses the movement available: only at the gym, daily, hourly, etc.

Positions all require different movement skills: sitting, kneeling, standing, leaning to the side, using arms when the body is oriented differently, etc

Places show how many environments the individual uses their movement skills: sitting on a park bench, airport waiting room chair, on a rock ledge, moving just in PT vs. at-home/in public.

We created a “MMOMO plot” to visualize how varied your movement is. The goal is to expand the shaded region in each direction as you experiment with new types of movement, exercises and places you practice movement.

We hope SCI athletes and trainers alike find inspiration in this discussion of movement variety to experiment with the motions they can do, experienced in new ways!

Explore these concepts in greater detail in our book, From the Ground Up: a Human-Powered Framework for Spinal Cord Injury Recovery, available in print & e-book format.

The role of fascia in SCI recovery

An essential component of our approach toward achieving great movement independence – the on my own part of the equation – is developing greater body-wide integration.

For us, integration is the use of many parts of the body in order to support the action in one area. This body-wide interdependence is how we are designed to function, and it is a critical component of how load gets distributed throughout the body and force is then exerted on that force..

By increasing integration and developing automatic patterning of this integration, individuals with paralysis can improve function dramatically. – without even requiring more neural connection!

Our extensive connective tissue network, know as fascia, surrounds every muscles, bone, organ and nerve in our body. Mechanical tension can be created in one part of the body and be felt anywhere else in the body. Thanks to this fascial network, we have direct mechanical link to areas that may be denervated after injury, making body-wide integration possible after spinal cord injury.

Fascial tensioning follows specific patterns, as dissected and described by Thomas Myers in his book, Anatomy Trains. We discuss these fascial lines, as they apply to SCI recovery, in great detail throughout our book, and hopefully this brief introduction encourages you to learn more about this fascinating connective tissue system.

Chapter / Episode 3 topics include:

There are as many post-injury goals as there are injured individuals

Our functional definition of recovery: Moving More On My Own (MMOMO)

*How* you move matters: places, types, frequency, positions

Self-supported & simple is better than externally supported & complex

Why anchoring stability is necessary in one region of the body for functional mobility elsewhere in the body

Fascia: what it is and why SCI athletes & trainers should care

Visualizing the human body as a tensegrity structure

Sign up for the FTGU Book Club to get these insights on spinal cord injury rehab delivered to your inbox every week, for ten weeks.