Chapter 9: Develop Patterns

This discussion + podcast is the ninth of a 10-part series that accompanies our book on SCI recovery, From the Ground Up: A Human-Powered Framework for Spinal Cord Injury Recovery.

It will introduce the uninitiated reader to topics discussed in Chapter 9 of the book, but some vocabulary or context may not be fully defined.

When someone says “lift with your legs,” “sit up straight,” and “walk with your head held high,” (whether you have an SCI or not) we can all pretty much picture the mechanics and posture that these cues encourage. They also all reference the idea that a singular movement – any movement – can be executed in a variety of ways: some more mindful and bio-mechanically efficient than others.

Some movement gurus might say that specific attention to alignment doesn’t matter too much, but when talking about SCI rehab, these subtle variations in mechanics and posture matter – they matter a lot. Remember, fascial communication relies on precise bio-mechanical alignment!

Our job (as a professional or individual with SCI) is to discover which ways of moving are most efficient and specific to an individual’s recovery. Interestingly, these “efficient” movement patterns may not feel as easy or helpful at the beginning – and can make us feel even less functional at times – but it’s important to remember how the investment helps in the long term.

What determines our movement patterns?

In other words, why do we sit the way we sit? Or transfer the way we transfer?

Movement patterns and postures, especially after SCI, are the complex result of:

Location and degree of paralysis vs. preserved muscle activation

Degree of intra-body integration (leverage of fascial tensegrity)

Chronic postures and repeated tasks (re-inforced postures)

Pain (avoidance of certain postures/movements)

Whatever feels good! (increased frequency to that posture)

Paralysis. Paralysis changes how you move even in unaffected areas since the torso and legs no longer provide the same support from below. The base of each posture is compromised, so the trunk and upper body must improvise. The drastic change in “strength” from one posture to another can be confusing.

Intra-body integration. If athletes better understand why and how they make compensatory adjustments, they can better re-integrate these disconnected areas. Even small increases in self-support can bring big improvements (and confidence) in daily tasks.

Chronic postures and repeated tasks. If you move or don’t move, in the same way for many hours every day, your body will conform to the demands of the (in)activity or posture. As tissues adapt over time to this position or movement, it becomes easier to repeat the pattern and will form a self-reinforcing cycle. Spending a disproportionately large part of the day seated will lead to tight hamstrings and hip flexors. A habit of leaning onto the center console while driving will create imbalances in the mobility and strength of the spine. On the other hand, people who kneel on the floor to dine or pray will generally have more range of motion in their hips as opposed to those who always sit at a table. These are persistent effects of chronic postures.

Pain. To avoid pain from an acute or chronic injury, you may start moving in a certain way. Whether the pain persists long-term or temporarily, this new “avoidance movement pattern” can persist long after the original injury has healed. The key is to re-introduce pressure and movement to the area as soon as it’s safe to do so.

Whatever feels good. This is the flip side of avoiding pain. You will gravitate toward whatever you perceive as satisfying. We say ‘perceive’ because you can teach yourself to revert to patterns that are biomechanically better, even if they are not necessarily easier. For example, you can teach yourself to perceive a slouched posture as less enjoyable than an upright one, even if sitting taller takes more effort. This is one way to use conscious involvement to bring about subconscious changes.

Explore these concepts in greater detail in our book, From the Ground Up: A Human-Powered Framework for Spinal Cord Injury Recovery, available in print & e-book format.

The motor development progression, applied to SCI rehab

Obviously, paralysis impacts how the body organizes movement. The sequence of activation that “makes sense” kinesthetically to an able-bodied individual is different from how a paralyzed neuromuscular system might approach the same task.

This illustrates an important aspect of training new patterns after SCI: intra-body integration won’t happen automatically. Just as we must go to great lengths to connect to areas of the body (Chapter 8), we must also consciously focus on how these connections interact to form complex and efficient patterns.

Fortunately for all athletes learning to move again, nature has given us a guide to repatterning in the form of motor development progression (MDP). These are the stages of movement-learning that all young children pass through on their way to walking.

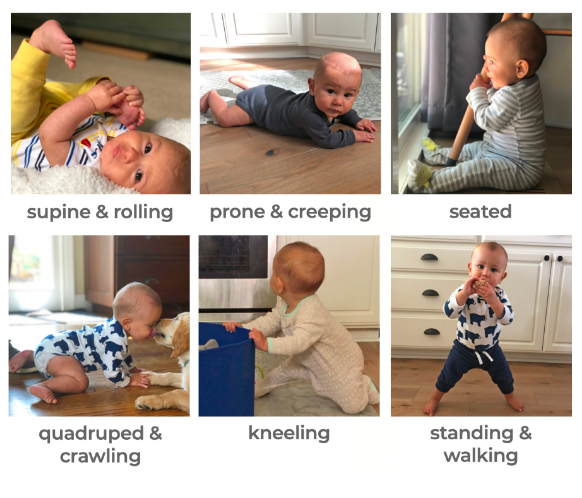

The stages of the motor development progression (MDP):

Supine

Prone

Side-lying

Seated

Low-kneeling

Quadruped

High-kneeling & split-kneeling

Standing & split-standing

Walking

It is impossible to overstate how important this concept is for SCI recovery: there is an order to movement acquisition, and it comes directly from biology.

The same motor development progression through which young children develop can be used as a guide for spinal cord injury programming!

Supine. The baby begins on his back, lying helplessly as he observes his parents’ movements around him. His eye movement leads to head rotation and eventually stretching and kicking his arms and feet. As he begins to grasp objects, perhaps putting them in his mouth, he lifts his head to look down at them. This supine position is the first use of the front line flexion pattern.

Prone. At some point, the baby follows the activity in the room with his eyes, then his head, to the side, and in order to keep watching, uses his arms and legs to roll over. Now face-down, he is forced to find a way to breathe and continue to look around while prone. He’s using the back line extension pattern for the first time.

Side-lying. As he gets better at rolling back and forth, he integrates more of his body, including the lateral line, into the side-lying parts of the floor-based motion. The spiral line rotational pattern gets stimulated with the rotation of the ribs and spine.

Seated. Independent sitting for the first time is a huge milestone. It requires engagement from all previous patterns for the baby to balance upright. Until this point, the torso has always had support from the floor along its length. Once seated, this support must come from under the pelvis and transmit up through the spine. While seated, a whole world opens up to the child, who can now see much farther than from the floor. This vantage point inspires action and a desire to locomote.

…and on this progression goes!

Notice that each stage builds on what comes before.

There is an order to learn the skills required for something as complex as walking – starting on the floor, and building from the ground up. When viewed developmentally, you can begin to see how all the postural pieces fit into a sequence that all SCI athletes can follow with their exercises. The MDP eliminates the haphazard, random feeling of programming which frustrates so many athletes.

Working through the MDP ensures that all the stability and mobility requirements of each posture are taken care of at each stage. Building postural control after SCI, from the ground up through the MDP, is the most accessible format of postural programming you can do!

Experience the motor development progression for yourself in our online, self-paced workshop:

Practical Posture for SCI: essential concepts & exercise sequences to build trunk control

Supplement these chapter cliff notes with audio of Theo & Stephanie discussing these topics.

Chapter / Episode 9 topics include:

Changing HOW you accomplish a task will unlock new abilities—even without additional neural connection

Invest in your environments for repetitive tasks now for long-term benefits

Patterning progressions from static>>effective>>dynamic postures

How to use the motor development progression as a rubric for pattern development

Transitions between postures are as important as the positions themselves for improving everyday activities!

Sign up for the FTGU Book Club to get these insights on spinal cord injury rehab delivered to your inbox every week, for ten weeks.